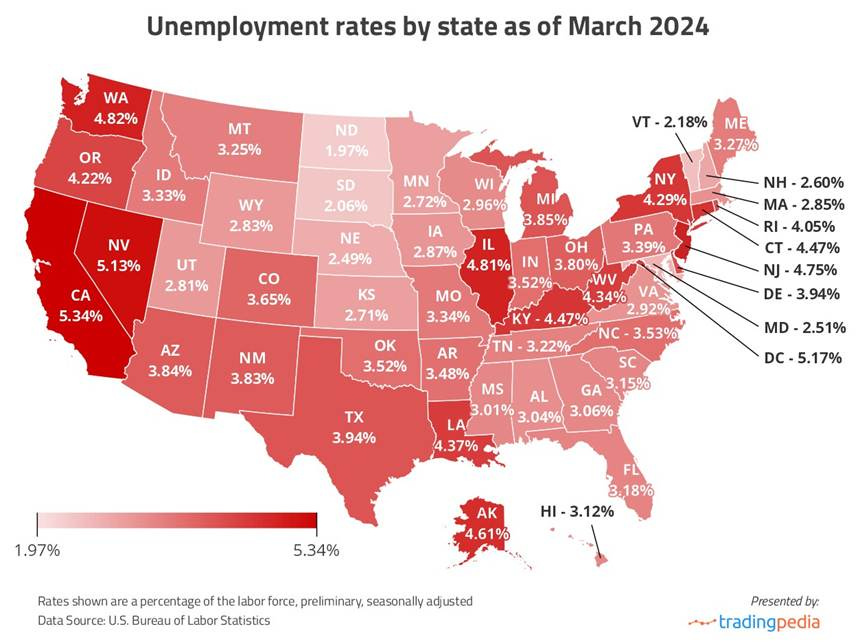

Congress’s new One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA, H.R. 1) imposes sweeping work requirements on Medicaid expansion adults. The law mandates 80 hours per month of work, community service, or job training to keep Medicaid coverage¹. Supporters claim this change “will stop the subsidization of competent adults who are just choosing to not work”². The above two illustrations indicate that there is only a weak tendency for states with very high Medicaid spending to also have very high unemployment rates, and vice-versa for very low spending and very low unemployment rates (Pearson r≈+0.62 among states with available data). The weak correlation here is consistent with the fact that there are many other socio-economic factors at play in determining Medicaid spending beyond unemployment rates at the state level. For instance, larger states naturally have larger total Medicaid budgets simply due to more people. California (39.5 M people) spent about $161 billion on Medicaid in FY202513, 14, whereas tiny Wyoming (0.58 M people) spent only $0.73 billion15 files.kff.org. Thus, total Medicaid spending is strongly positively correlated with population size (r≈0.99) because more residents mean more Medicaid enrollees. State unemployment, however, shows no strong linear link to population size (r≈0). In fact, many very small or rural states have some of the lowest unemployment rates, while some large/dense states have higher rates. North Dakota and South Dakota (populations ~0.77 M and 0.89 M) had the nation’s lowest jobless rates (~2.0–2.1% in early 2024)16, whereas California (pop ~39.5 M) had the highest state unemployment (5.3%)16.

Furthermore, in reality, nearly all working-age Medicaid recipients who can work already do³. Data show only a tiny fraction of those enrollees are unemployed by choice; most are not working due to factors like illness, caregiving, or lack of available jobs. In short, the premise that able-bodied people on Medicaid are “idle” is false³.

Medicaid work requirements: OBBBA forces able-bodied expansion enrollees to meet an 80-hour-a-month work/volunteering rule¹. Those searching for jobs or facing barriers (transportation, training) would lose coverage if they fall short.

Myth vs. reality: Lawmakers argue this punishes “choosing not to work,” but studies find almost 92% of eligible, non-disabled expansion adults already work³. Only about 8% are unemployed, often older women or those with health limitations³.

Coverage losses: The Congressional Budget Office projects the reconciliation bill will cut Medicaid enrollment dramatically – roughly 11.8 million more people uninsured by 2034⁴. Most of that increase comes from these new work mandates.

Hurt the vulnerable: The requirements especially risk stripping coverage from people with real challenges. For example, over 2.6 million adults with disabilities (not on SSDI/SSI) would struggle to meet an 80-hour rule¹.

In effect, OBBBA punishes involuntary joblessness. Experience with similar programs shows these mandates often reduce coverage without creating jobs⁵. Research on Arkansas’s Medicaid work reporting found large drops in enrollment but no rise in employment⁵. The takeaway: moving people out of Medicaid for “non-work” does nothing to fix unemployment – it only removes health care from people in need.

My Experience: At-Will Employment and Unemployment

My own career illustrates this problem. I am not lazy or unwilling to work – on the contrary, I have always sought employment – but I lost jobs through no fault of my own. In the U.S. “at-will” employment system, employers can fire workers for any reason or no reason⁶⁻⁸. In practice, this means one can be suddenly laid off during a company reorganization, without warning or justification. The lay off need have nothing to do with a person’s performance; it can simply be the result of a cost-cutting decision. Under at-will law, there is no recourse for the person who was laid off.

Such abrupt, unjustified terminations are common. As the National Employment Law Project notes, in the U.S. “most workers” can be fired “without warning or explanation,” creating an extreme power imbalance⁷. This insecurity forces employees to accept poor conditions (low pay, long hours, unsafe workplaces) for fear of being fired. It also means any termination – even if unfair or discriminatory – counts as a voluntary “disqualification” under work mandates. In other words, Americans can find themselves unemployed not by choice, but because the employer’s whims or mistaken business judgments made them disposable.

Importantly, the U.S. model is unusual. Most developed countries require just cause for firing. For example, under German law a dismissal must be “socially justified” by valid reasons (like poor performance or company downsizing)⁹, and Japanese courts demand that firings be “objectively reasonable and appropriate”¹⁰. Even in the U.S., Montana is the only state with a “good cause” protection: after a probationary period, an employee can’t be fired without justification¹¹. These examples show it’s possible to ensure job security – but Congress chose not to address at-will at all.

Instead, OBBBA effectively penalizes victims of at-will firing. One such penalty after being let go is suddenly having no income and potentially having a genuine need for Medicaid assistance. Now under OBBBA, even actively looking for a new job might not save a person’s healthcare coverage if their job search takes more than a month or so. It feels punishing: it treats someone who lost work involuntarily in the same way as someone who refused a job offer. My experience, and countless others’, shows unemployment often stems from the loss of work opportunities, not personal choice.

Better Solutions: Job Security Over Benefit Cuts

Cutting health care is not the answer. To truly help unemployed Americans, policymakers should strengthen job security and support, not punish people for losing work. Experts recommend reforms like:

Just-cause protections: Laws requiring employers to have legitimate, documented reasons before firing. For instance, New York City’s proposed Secure Jobs Act would ban “unfair and abrupt” firings¹². Studies find just-cause laws are broadly popular and improve worker stability¹². They protect employees from arbitrary or retaliatory dismissals (e.g. for complaining about safety or discrimination)¹².

Collective bargaining & contracts: Union representation and fixed-term contracts give workers more power and security, reducing the impact of single-termination events. These models already exist in many sectors.

Supportive services: Instead of mandating work, invest in childcare, job training, transportation, and placement programs. Research shows that providing support yields better employment outcomes than punitive mandates. (By contrast, punitive work requirements merely add red tape and scare people off coverage⁵.)

By focusing on job stability and opportunity, we help people stay employed. This approach addresses the root causes of unemployment. Stricter job protections (as seen in Europe and parts of the U.S.) would prevent many layoffs in the first place. In sum, it would be far more effective to eliminate the at-will loophole and mandate just cause than to strip Medicaid from workers through harsh work rules⁶⁻⁸,¹².

Conclusion

The OBBBA’s strategy – blaming the unemployed and cutting their benefits – is misguided. It rests on the false idea that joblessness is a choice. In truth, the law’s harsh work requirements punish people who lost jobs through no fault of their own. A more fair and efficient solution is to ensure that stable, secure employment is available – by replacing at-will dismissal with true job protections and by bolstering support systems – rather than by denying health care to those between jobs.

References

Congress.gov. (2025). H.R. 1 – One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1

The Guardian. (2025, July 3). Trump’s big bill achieved what conservatives have been trying to do for decades. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jul/03/trump-spending-bill-conservatives-law

American Progress. (2025, July 3). 10 egregious things you may not know about the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/10-egregious-things

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2025, June 4). Breaking down the One Big Beautiful Bill. https://www.crfb.org/papers-breaking-down-the-one-big-beautiful-bill

AP News. (2025, July 3). House passes Trump’s signature bill, sending it to the president’s desk. https://apnews.com/live/donald-trump-news-updates-7-3-2025

Wiley, R. (n.d.). Employment at will. Rob Wiley, P.C. https://www.robwiley.com/employment-at-will.html

National Employment Law Project. (n.d.). Hear us: Cities are working to end another legacy of slavery— ‘at will’ employment. https://www.nelp.org/cities-are-working-to-end-another-legacy-of-slavery-at-will-employment/

Roosevelt Institute. (n.d.). To build worker power, end at-will employment. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/to-build-worker-power-end-at-will-employment/

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July). At-will employment. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/At-will_employment

Boise State University Press. (n.d.). What are alternatives to employment at will? Business ethics: 100 questions. https://boisestate.pressbooks.pub/businessethics/chapter/what-are-alternatives-to-employment-at-will/

Betterteam. (n.d.). At-will employment. https://www.betterteam.com/at-will-employment

Thomson Reuters. (n.d.). What is at-will employment? Insights for employers. https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/insights/articles/what-is-at-will-employment

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). List of U.S. states and territories by population. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 5, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_population#:~:text=Image%20California%201%2039%2C538%2C223%201,Pac

Ibarra, A. (2025, March 26). Republican districts may be hit hardest by Medicaid cuts. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/health/2025/03/medicaid-cuts-republican-districts/

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). List of U.S. states and territories by population. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 5, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_population#:~:text=Image%20Wyoming%2050%20576%2C851%2050,Mtn

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024, April 19). Regional and state unemployment, March 2024 (USDL-24-0662). https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/laus_04192024.pdf